As we walked across Forsyth Street last October during one of the hundreds of tours last year, someone asked if I had read Nine Days? “No, what book is that?” I responded. They said “it’s the story of the nine days of Martin Luther King’s life that started right there that changed the course of American politics” as they pointed up Forsyth and under what was then the Crystal Bridge. From 1948 to 1991, Rich’s Department store had a Christmas tree lighting on the Crystal Bridge that made headlines in several ways.

Immediately, I pulled out my phone, searched for it, read the title and added it to the Kindle on the spot and kept on with the tour.

I had known the broader details of Dr. King starting the sit-in’s in Atlanta in 1960 after trying to get into the Magnolia Room – Rich’s private dining room. However, like many stories condensed in one paragraph on a tour, there was so much more to the story. Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King’s Life and Win the 1960’s Election communicates the complexities and politics at that moment From back room calls to the perception of support, to the technicalities of the law, all of this in the middle of the race for the White House. Dr. King’s nine days in October unquestionably changed American politics up to present time today.

On this blog, I’ve covered MLK’s finest moment in Atlanta and learned from his main lieutenant Ralph David Abernathy how the movement was strategized, timed, and executed. However this moment in history is impactful for several reasons: first, it’s a continuation of MLK Jr. being pulled to the national stage – the first was at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery where boycott bus planning occurred after the arrest of Rosa Parks. Second, it’s the first time the preacher’s son is arrested and jailed in Atlanta. Third, it sets the foundation for the future moments on the national stage including the March on Washington in 63’ and the Voting Rights Act of 65 and the eventual shift of American politics.

This chapter starts on Forsyth street on October 19th, 1960. At this point, sit-in’s were occurring across the Southeast starting first in February at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, NC earlier that year. MLK Jr. moved his family from Alabama to Atlanta in early 1960, where his father, Daddy King was the paster at Ebenezer. Daddy King preached at Ebenezer Baptist Church from 1931 to 1975. As his son returned from Alabama, Daddy King promised his friends and the community that “he’s not coming to cause trouble.”

Even more surprising to me was the national political climate and how the Democratic and Republican vote was split evenly in 1960 among Black voters. Here’s an excerpt:

“Nationally, surveys at the time showed that Black Americans were split on the question of which party was better for them, narrowly favoring the Republicans. Roosevelt’s New Deal had indeed swayed many formerly staunch Black Republicans through job creation, particularly in the North, but Black communities in southern cities like Atlanta remained GOP strongholds. Atlanta’s Black Republicanism was more than a residual memory of Lincoln. With a southern Democratic Party that fiercely protected its segregationist power, allegiance to the GOP was a matter of survival for families like the Kings. Yes, FDR had made the party more palatable in many Black communities, but here in the South, men like Daddy King were only being attentive to the reality they saw around them.”

Kendrick, Stephen; Kendrick, Paul. Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.'s Life and Win the 1960 Election (p. 43).

Additionally:

In December 1959, King junior told a friend how Nixon was the only candidate who would call him and invite him to his home, which made him inclined to support Nixon, as he thought increasing numbers of Black Americans would. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy, King’s close friend, had already made clear that Nixon was his man. King voted Republican in the 1956 presidential election, as did nearly 80 percent of Atlanta’s Black voters. In addition to his father, other leaders whom King had respected all of his life such as the real estate broker John Calhoun—head of the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP and a wily Republican wheeler-dealer—held a modicum of political power by way of the organizations they had built with the support of Black Republican voters. But men like Calhoun did not operate in this political world on their own; they needed the power of Black preachers.

(p. 44)

To add even more context to where the political playing field stood, here was the reception of then Vice President Nixon in Atlanta in August of 1960.

“For generations, Republican candidates had hardly bothered to visit the solid Democratic South, but as this campaign season began, Nixon decided he would challenge Kennedy anywhere and everywhere he could. He scheduled a campaign stop in Atlanta for the late summer, and the turnout on August 26 staggered even the Nixon team. The vice president was exhilarated at the unexpected sight of between 150,000 and 250,000 Georgians cheering for him, spilling out of Five Points to Hurt Park on Edgewood Avenue and up Peachtree Street. Never in his meteoric political career had he seen anything like this, and any observer couldn’t help but wonder, could the South be the future of the Republican Party? In 1956, Eisenhower had been the first Republican since 1928 to gain a majority of the South’s electoral votes, but he was a popular general and had won nationally in a blowout. Was it possible to build on that momentum, especially since the Democrats had nominated a young Roman Catholic from Massachusetts? The Alabama newspaper columnist John Temple Graves II had written to Nixon, “The South is the wave of your future.” Graves advised, “The political answer for Republicans is to cater no longer to a labor and Negro vote they can’t get but to a southern one they can get—if they have the courage.”

(p. 35)

Fast forward to the summer of 1960 in Atlanta. Lonnie King (no relation to MLK Jr.) said to MLK Jr. ““Can I get you to go to jail with us? ’Cause if you go to jail with us, because of Montgomery, it will become an international story.” The plan, he said, "was to stage a sit-in at Rich’s."

Rich’s Department store was the commerce and retail gravitational force in Atlanta for over a 100 years. The best book I’ve read studying Rich’s history is Rich’s A Southern Institution. In 1960, the iconic department store set the example for all department stores in Atlanta. Dick Rich, the president, believed himself to be progressive on the race issue demonstrated by being the first store to offer Black shoppers charge cards. However in the summer when Lonnie King went into the Rich’s lunch counter, Rich’s staff turned off all the lights and closed the restaurant to avoid any conflict. When police brought Lonnie into the station, Dick Rich met Lonnie there and demanded he not to protest at his store.

According to Nine Days:

“Lonnie responded that Rich needed to integrate his store fully, even allowing Black shoppers to eat in the elegant Magnolia Room. The meeting fell apart, and Rich’s face turned red as he shouted, “If you bring your Black ass in again, I’m telling you, Chief, put his ass under the jail.” Lonnie shot back, “I’m coming back in October, and I’m going to bring thousands of students with me, so Chief Jenkins, get your cells together, ’cause we will be back.”

(p. 49)

Fast forward to October that year and after the 3rd staged debate between Nixon and Kennedy, the time to act was now. At the time, Martin Luther King Jr. was a 31 year-old pastor. Students were pressuring MLK Jr. to join the upcoming Rich’s sit-in. Daddy King highly disapproved of it as this was something students did. MLK Jr. initially had no plans to join this sit-in as his schedule called for him to be in Miami delivering a speech – this one would potentially include both Presidential candidates, however that event never came to fruition leaving King’s schedule open.

King confided in his old friend why he really wished for the Miami event to take place: “I’m in a real jam ’cause they’re going ahead despite my urging them not to do a sit-in before the election; they’re going to go ahead and do it for Rich’s department store. I’m under great pressure to go there. I don’t really want to, I don’t think it’s the best thing, but they’re doing it and I probably am going to have to go with them.” King had wanted a good excuse to avoid the Rich’s protest, which being in Miami would have provided, and now it had been yanked away. He felt boxed in by students whose idealism matched their determination. Without an important event to attend, King conceded, “I have to participate now.”

(p. 55)

The day before the sit-in, Lonnie King had MLK Jr. on the phone along with Daddy King who was doing most of the talking, reiterating his son would not be joining the sit-in. One of the reasons Daddy King was so adamant at this son’s participation was the prior legal entanglement MLK Jr. had which included baseless claims around fraudulent taxes and what was seemingly an innocent traffic ticket.

On May 4, 1960, King volunteered to drive the novelist Lillian Smith, a white ally of the movement, to her breast cancer treatment. DeKalb police spotted this Black man and white woman in a 1957 Ford near Emory University’s campus on Clifton Road and pulled King over. As he sat in the driver’s seat, the police told King his car tags were out of date, though Smith knew that her presence was the real reason why her friend had been pulled over. King explained that the car did not belong to him. The officer ticketed him for this and then, fatefully, also wrote him a ticket for not carrying a Georgia driver’s license, though he still carried a valid Alabama one. King took a day off to appear before Judge Oscar Mitchell in nearby Decatur, and in a quick and seemingly uneventful trial he was ordered to pay a twenty-five-dollar fine, which he paid.

(pp. 57-58)

The persuasion by Lonnie King came to a crescendo when he quoted Daddy King’s recent sermon “you can’t lead from the back, you’ve got to lead from the front.” That was the pivotal moment on the call that moved MLK Jr. into the sit-in the next day:

Daddy King could say nothing to that. His son slowly replied, “L.C., what time do you want me to meet you?” “Ten o’clock on the bridge.” This was the sky bridge over Forsyth Street that led into Rich’s. They all knew it well. “Okay,” King said. “I’ll be there.”

October 19th, 1960 had the following cultural moments and influences: Sam Cooke’s “Chain Gang” and Ray Charles “Georgia on My Mind” were constantly played on the radio. Georgia quarterback Fran Tarkenton would lead the Georgia Bulldogs in Saturday’s game that weekend, and Inherit the Wind and Ben-hur were on the silver screen as the new musical Camelot just hit Broadway.

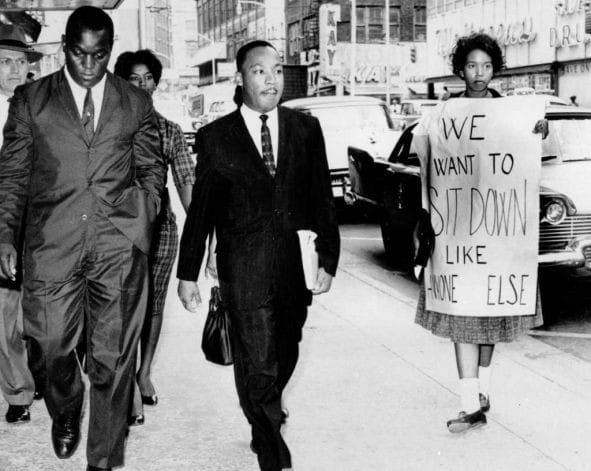

With a bible under his arm and dressed in his usual dark suit and tie, MLK Jr. met Lonnie and several other students at 11:00 a.m.. They started on the 2nd floor at the snack bar. When Rich’s employees saw the plan, they began shutting down everything.

Rich’s department store was not the only focus, “student teams hit other sites. Four national chain stores, Woolworth’s, Grant’s, Kress, and McCrory and McLellan dime stores, had announced that they were integrating lunch counters in more than a hundred cities, but Atlanta had not been on their list. Demonstrators found “Closed” signs posted up and down Broad Street.”

As word spread of the sit-in counter protesters began to mobilize with Ku Klux Klan members arriving in droves.

The students and Dr. King turned from the 2nd floor lunch counter, up to the crown jewel of Rich’s, the Magnolia room, an ante-bellum themed private restaurant. Observing the entire plan was Donald Hollowell, a war veteran and 42 year old lawyer for the students and the movement. As Dr. King made his way to the Magnolia Room, more Rich’s employees gathered as did the police Captain. When Captain Little communicated they were breaking law and he would have to take them away, Lonnie said, “I came here to eat, and prefer to be arrested than not be served.” With that, Captain Little declared all four now under arrest including Dr. King.

It was there that Captain Little arrested Lonnie King, MLK Jr. and others. Neither of them had been put in handcuffs, likely on the order from Mayor Hartsfield. Once word got out that students were being arrested at Rich’s, students from the other department store made their way to the Magnolia Room.

“Fifty-two protesters had appeared in Judge Webb’s court by the end of the day. Lonnie was proud of the number of students arrested, with thirty-six ultimately heading to jail—nineteen women and seventeen men—and sixteen students released. Before they could be transported to the two month old Fulton County Jail, students were held near the courtroom downtown at Fulton Tower—the city jail known as Big Rock.”

(p. 77)

In contrast to the Fulton Tower, the students couldn’t believe the “brand spanking new” look and feel of the new jail.

Now with MLK Jr. in jail, the web of communication, decisions, media coverage, and legal interpretations kicked into full gear – all three weeks before the election of 35th President and still several days away before this situation makes it on the radar of any Presidential candidates.

Back in DeKalb county just east of Fulton County, where Emory University calls home, Judge Mitchell, the same judge who gave Dr. King a suspended traffic sentence, notified authorities that Dr. King was a wanted man. Unbeknownst to MLK Jr., this put him in much graver peril.

The court system was overwhelmed and slammed the next morning after the initial arrests. More students had been arrested and the pressure on the Mayor, courts, and business community all mounted. The AJC had questioned why neither Presidential candidate had made a statement yet.

When Kennedy was pressed that day while in New York his response was a suggested White House conference on civil rights to get legislation passed. Nixon had spent years crafting a narrative as a racial moderate, through criticism of segregation and voiced dissatisfaction in the late 50’s of legislation that made the right to vote tougher. This was the Nixon MLK Jr. and his father knew, but he neither made statement.

On the third day, more students lined up outside of Rich’s. All the other downtown stores with lunch counters had shut down. Hartsfield was swamped with inbound messages and yet he had little power in the situation as the trespassing law that the students and King were arrested for was a state law.

That night, during the 4th and final debate, neither candidate said anything of substance about civil rights nor the growing situation rising in Atlanta.

John Lewis said of the election, “I didn’t care for either man, nor did most of my friends. In fact, none of us cared much about the presidential race at all.”

(p. 109)

Mayor Hartsfield had business leaders from both the Black and White communities together attempting to get them all focused on a 30 day stop to protesting so they reach a formal agreement as well as get Dr. King Jr. out of jail. A team member on the Kennedy campaign made a discovery call to an Atlanta lawyer he knews from years prior to obtain information about the situation down in Atlanta. The Atlanta lawyer drove down to City Hall and mentioned the call to Mayor Hartsfield. That action alone gave Mayor Hartsfield enough substance to stretch the truth.

“He [Hartsfield] walked confidently back into the chamber to tell the Black leaders, “I will turn Martin Luther King loose, and I want you to know that Senator Kennedy has evidenced his interest in this thing. He has phoned me to help get a peaceful settlement, and he has also asked me to turn Martin Luther King loose.”

(p. 117)

This announcement spurred Black Nixon supporters in the meeting with the Mayor to reach out to the Nixon campaign and get them to act. When media began publishing Hartsfield’s announcement about Kennedy’s involvement (with no knowledge from the candidate or the senior campaign officials), local supporters of Kennedy who had been his eyes and ears, were irate and wanted to know who was the Kennedy campaign associate helping King get out of jail. Hartsfield admitted he “ran the ball further than expected and that needed a peg to swing on and he swung on it.” The Kennedy campaign member who associated the campaign with King thought he would be fired but got a strong reprimand instead.

Now Mayor Hartsfield had to get the students out of jail and he went straight to Dick Rich, the president of Rich’s. After a long back and forth, Hartsfield got Dick to drop all the charges including the ones on King Jr.

The next day, Day 5, a Sunday, headlines in Atlanta asked “Did Kennedy Man Ask King Release?” Hartsfield had pulled back his story connecting the Kennedy campaign and later clarified it was a call from Washington. Regardless, after the dropping of charges, the slapped hand from the Kennedy campaign liaison, and the soon-to-be release of MLK Jr., the chapter would soon find its closure.

There was one small, outlining factor that was about to put the entire situation into overdrive. Judge Mitchell over in DeKalb county believed that due to King’s suspended sentence, his county had the right to bring King into custody before Fulton County freed him. No one was paying attention to this but Daddy King’s instinct had been correct.