If you happen to walk, bike, scooter, or drive by South Broad Street in Atlanta, Georgia anytime between today and the next 4 months, there’s a good chance you’ll see hundreds of construction workers re-stacking bricks on a commercial street that has been around since Atlanta’s earliest days. We actually just found a bottle of a “Globe Flower Cough Syrup,” which was one of the concoctions created before John Pemberton created Coca-Cola. See the bottle glued back together here.

The city is fortunate that these buildings were so forgotten, they were forgotten to be torn down. Through our work in South Downtown, we are able to dissect, restack, restore, and even pour new concrete for these buildings on S Broad Street.

The purpose of this blog post is to share why revitalizing a historic downtown rarely happens in America anymore and how the costs associated with such a revitalization incentivize developers to tear buildings down and put up more economical structures.

I’m also going to do my best to not divulge into all the history that has occurred on S Broad Street over the years or else this post would be thirty thousand words. For quick context, this street in Atlanta has been the most glamorous and the most destructive since Atlanta’s founding. For decades S Broad Street was the commercial capital of the South with Rich’s magnificent and opulent department store titled the “Palace of Commerce” sitting center stage starting in 1924. By the year 2010, according to a Captain in the APD, S Broad Street had more homicides on it than any other street in Atlanta.

For first time readers, a German development group started the arduous process of buying every building on S Broad Street in 2016. In 2023, after investing over $200M, steering the ship for 7 years – through a global pandemic – they tapped out and walked off the property in March of 2023. David Cummings texted me and a few other entrepreneurial friends notifying us that 10 city blocks, 16 acres, and 50+ historic buildings were about to go to the courthouse steps. Author Josh Green has a more comprehensive review in Atlanta Magazine if you want to get more of the back story.

Several of those 50+ historic buildings happen to be on S Broad Street. It’s important to note when I write the word “historic,” it’s not just because they look old and have some chipped brick. The whole area of South Downtown is a Georgia National Register Historic District titled: Whitehall Street Retail Historic District. There is a fascinating 34 page PDF for any extra curious readers on the buildings, architecture, and neighborhood history.

For the sake of this blog post, we are focused on S Broad Street in between Mitchell Street and MLK Jr. Drive. This is a true city block. We believe it has the opportunity to be Atlanta’s urban, historic crown jewel. The low-rise, human scale main street fosters an ideal environment for serendipitous interactions, walkability, and genuine community to occur. When you’re building a start up district, you want to create petri dishes for creativity and produce environments where people can align the neurons as quickly as possible.

Enough startup mumbo jumbo, let’s get into the economics. Commercial real estate, the buying and selling of buildings, is very new to me. When we look at how South Broad got to where it was and we take out the complex social, city, and infrastructure dynamics (which all need to be studied intently as an example), we get down to the brutal economics.

Unlike residential real estate, which is the main context I’ve viewed any real estate, commercial real estate is much different. Commercial real estate revolves solely around Net Operating Income (NOI). To keep it simple, NOI = Effective Gross Income (EGI) - Operating Expenses. Effective Gross Income is predominantly from tenants paying rent and operating expenses range from property taxes, insurance, utilities, repairs / maintenance, janitorial and trash removal, etc.

When all of that is calculated you get an NOI number. In commercial real estate, this is the most important metric. The value of the building is not the physical building, it is the income stream (or the NOI) of that building. This is a significant construct to understand if you ever buy a commercial building.

If we have a tried and true NOI figure, we can achieve the value of the building. The value of the building revolves around the “cap rate.” The cap rate is a negotiated and agreed upon number between you and the bank (or lender). For example, if the cap rate is 5% and the NOI of the building is $100k a year, then the building will be worth $2M ($100,000 / .05 = 2M). Here is where it can get confusing: the higher the cap rate, the less valuable the building. So if the building owner and banker / lender agree on a 7% cap rate, the building would be worth $1.4M (100,000 / .07 = 1.4M).

For the sake of this example, let’s assume you and a bank agree on a cap rate of 5% which would mean the area is stabilized and there are credible comparisons around the building to warrant a number – not the case today in South Downtown today. Regardless, in Q3 last year, the average loan-to-value for a commercial property was 63% with an interest rate between 5%-7% for a 5 year term.

Quick math: 63% of $2M is $1.26M of “loan” to “value” ($2M) with a 6% interest rate. This means you would have to cough up $740k to purchase the building with a $75,600 ($1.26M x .06) annual payment to the bank for 5 straight years and then you’d pay them back the full $1.26M or refinance (get another interest-only loan).

A $2M dollar building with let’s say 10k of leasable sqft is a cost basis of $200/sqft. With $100k of NOI, you’d need to charge your tenants, as a reminder, Net Operating Income = Effective Gross Income (EGI) - Operating Expenses. On average, operating expenses are 45% which means NOI is 55% of EGI. In this example of 100k NOI, you’d need to charge your tenant(s) $181k (100,000 / 55%) or $18 sq/ft – what a bargain!

Sounds simple and achievable right? However, what if the building you bought was over 120 years old? Now your tenant would be moving into a building that is 120 years old with 120 year old problems.

The easier solution would be to tear it down and build something modern and maybe a bit more economical – but now you’re tearing down historic buildings that can never be re-built like the original; the charm and magic erode away. But let’s play out that scenario.

If you wanted to tear down a historic 10k sqft building and construct a new 10k square foot building in an urban downtown, the cost would likely range from the low end of $300 sqft to the high end of $800 sqft So anywhere between the very wide range of $3M to $8M – for hard costs – to build a 10k sqft building. Hard costs include materials, labor, GC fees. Soft costs are approximately 25-30%; now the building has shot up to $4M-$10M. Of course, the numbers get much better if you go higher than two stories, which is why two story, human scale buildings rarely get built in urban cores anymore. Either way, all in, a phenomenal, stunning 10k sqft building could be built for $10M and just to err on the side of supreme caution, let’s bump it up 20% to $12M, so now our new price per square foot all in is $1200 psf. This building would approximately match the highest end build in Atlanta. I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the zoning restrictions that would be layered on with a new build. I can hear Eric Kronberg's voice, founder of Kronberg Urban Architects and our Broad Streets architects, commenting on this post if zoning restrictions were not even mentioned!

A bit more applicable to our current plan, let’s say instead of tearing down the old building, you work with what you have. You could rent the historic 10k building out as Class B or Class C commercial space for $20-$30 psf – assuming it was up to code which is a large assumption.

Or, you could invest in the building. What does investing in a 120 year old historic building that is human scale look like? Brutal economics.

The five most expensive problems we’ve found across the 57 historic buildings purchased in South Downtown are the following:

- Structural repairs and reinforcements. We actually had to do even more reinforcement of the Atlanta Tech Village at the historic Sylvan Hotel after we already moved in.

- Hazardous material abatement. Lead paint, asbestos, mold and more have pervaded the buildings across South Downtown. Fortunately, South Downtown is in a brownfield program which provides tax credits against the cost to produce the abatement work.

- Mechanical system updates. Every building requires new HVAC, plumbing, and electrical. Since most of these buildings haven’t been occupied in 10-50 years, there is no way to reuse anything. They also need all new connections to city infrastructure.

- Code compliance and safety upgrades. Fire code updates are non-negotiable laws and mandates. ADA compliance is mandatory for public/commercial use as well.

- Facade and historic preservation. So many of the buildings had layers of paint, graffiti, chipped facades, broken or warped brick that led back to number 1 (structural repairs).

These are only the top 5 most expensive rehab areas.

If we take the average per square foot number above (exclude the abatement due to the Brownfield program) we’re looking at approximately $400 per square foot to fully gut and rehab a “normal” historic building with “manageable” problems.

South Downtown is a completely different beast.

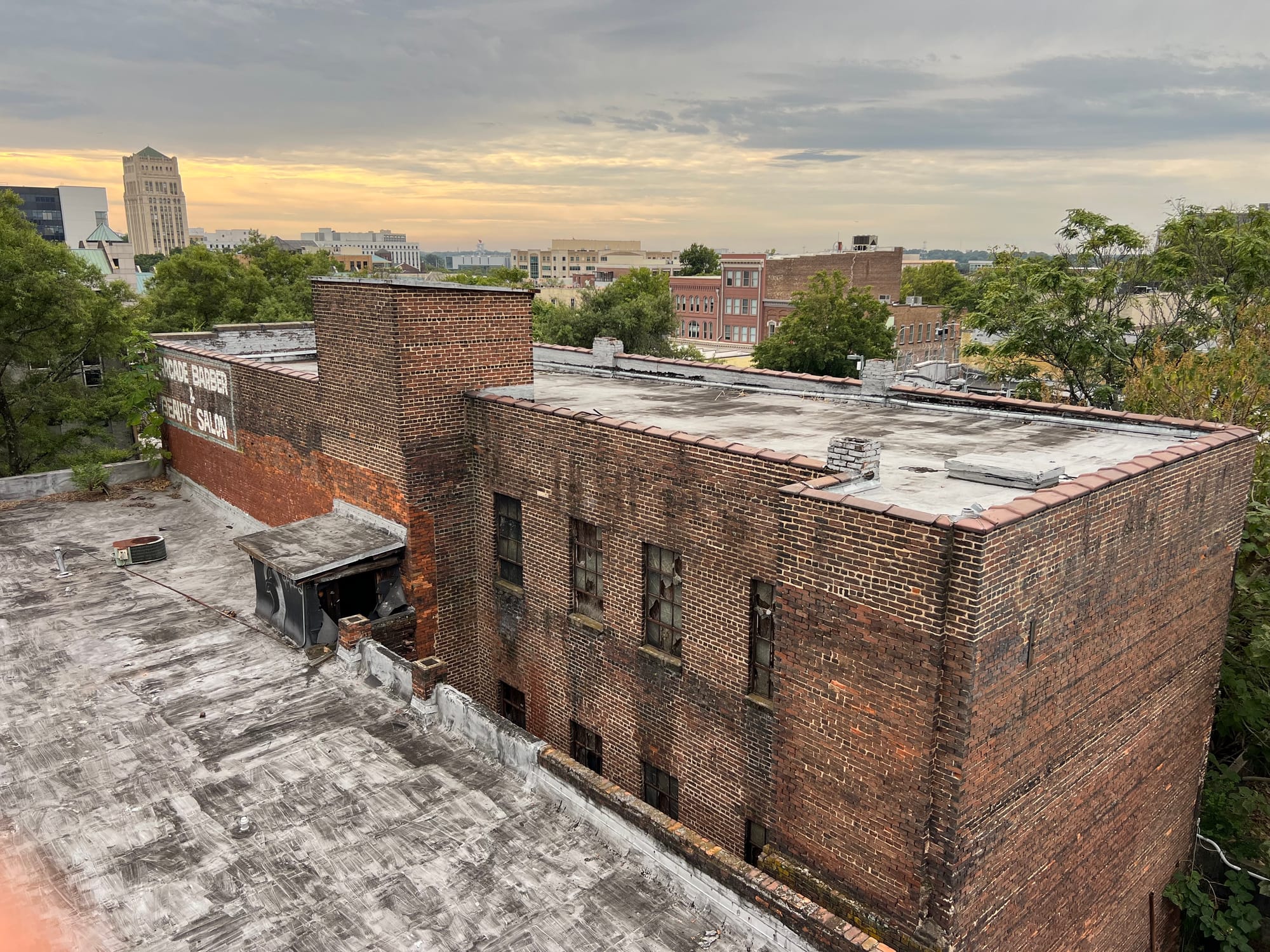

All the buildings on South Broad Street were in such horrid conditions, the per square foot number is much higher. Each building was so destroyed structurally, they needed full structural reinforcement or replacement. Every roof had leaks, holes, and rot where new roofs were required.

The largest challenge on the development side has been the astronomical costs to gut, rehab, and rebuild the buildings, particularly on Broad Street. They are the oldest we have and have the most challenges.

Here are some photos before the construction:

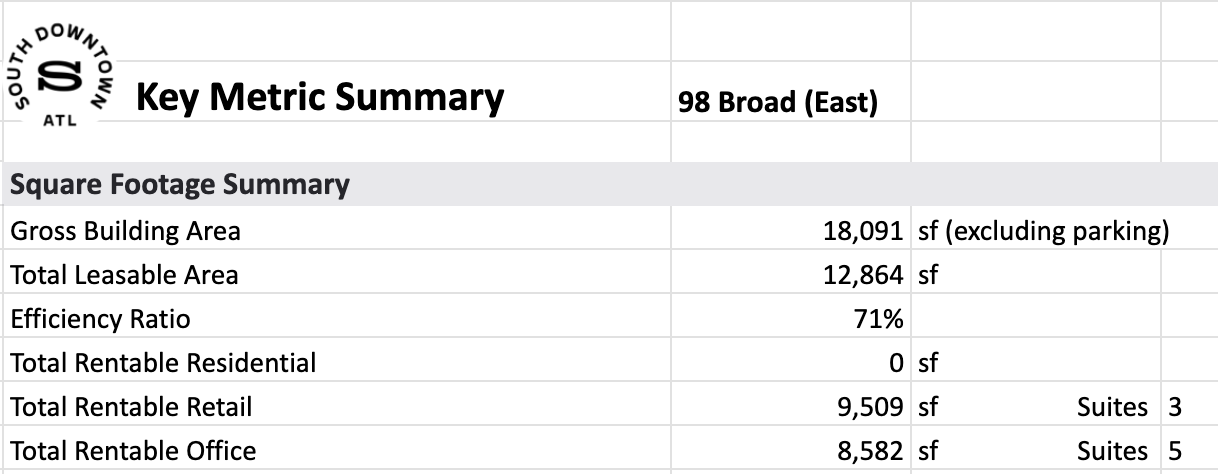

Like we have done before with the residential units, let’s get into the nitty gritty of South Broad Street.

South Broad Street includes South Broad Street East and South Broad Street West. Both streets have history dating back to Atlanta’s founding days. We believe most of these buildings were built in the late 19th century, early 20th century. The models below include 5 different buildings on Broad Street East. Below is a picture pre-renovation of Broad Street East. Winter Johnson general contractors are doing all our work on Broad Street.

There are five buildings we consider Broad Street East including the far right, non-historic one-story building. Below begins the model. This looks like six, but the one story building on the left has been hollowed out and is in the process of being made a courtyard due to the fully collapsed roof.

Office and retail are the plan for Broad Street East. We have Broad Street BBQ coming in on the retail side.

The office space rent in downtown Atlanta ranges from, as mentioned above, starting with C class rents around $20 psf and topping out on the very, very high end around $40 psf. This includes top line amenities and a new build.

The big question on a historic downtown in the urban core: will Atlantans want to work in a walkable, human scale environment where there is considerable dialogue with the streets?

This is very different from the generation before us.

My mother worked at the Tower of Power, Georgia Power’s HQ, off Ralph McGill for two decades before moving over to Southern Company’s HQ off Ivan Allen Jr. BLVD. She, along with thousands of Ga Power employees, would drive to downtown Atlanta, park in the protected and gated parking garage, and walk into the concrete and glass fortresses.

We’re building the opposite experience.

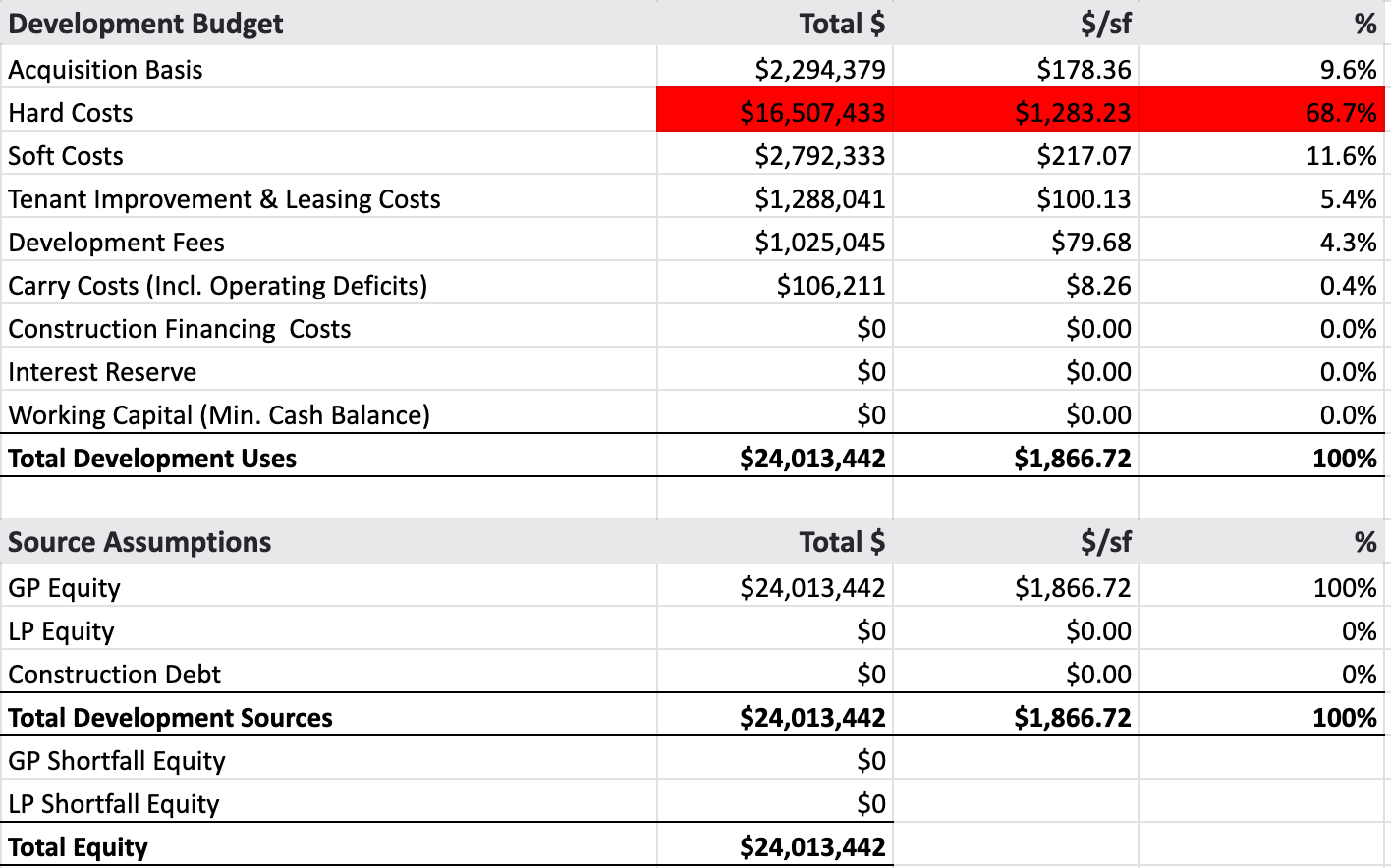

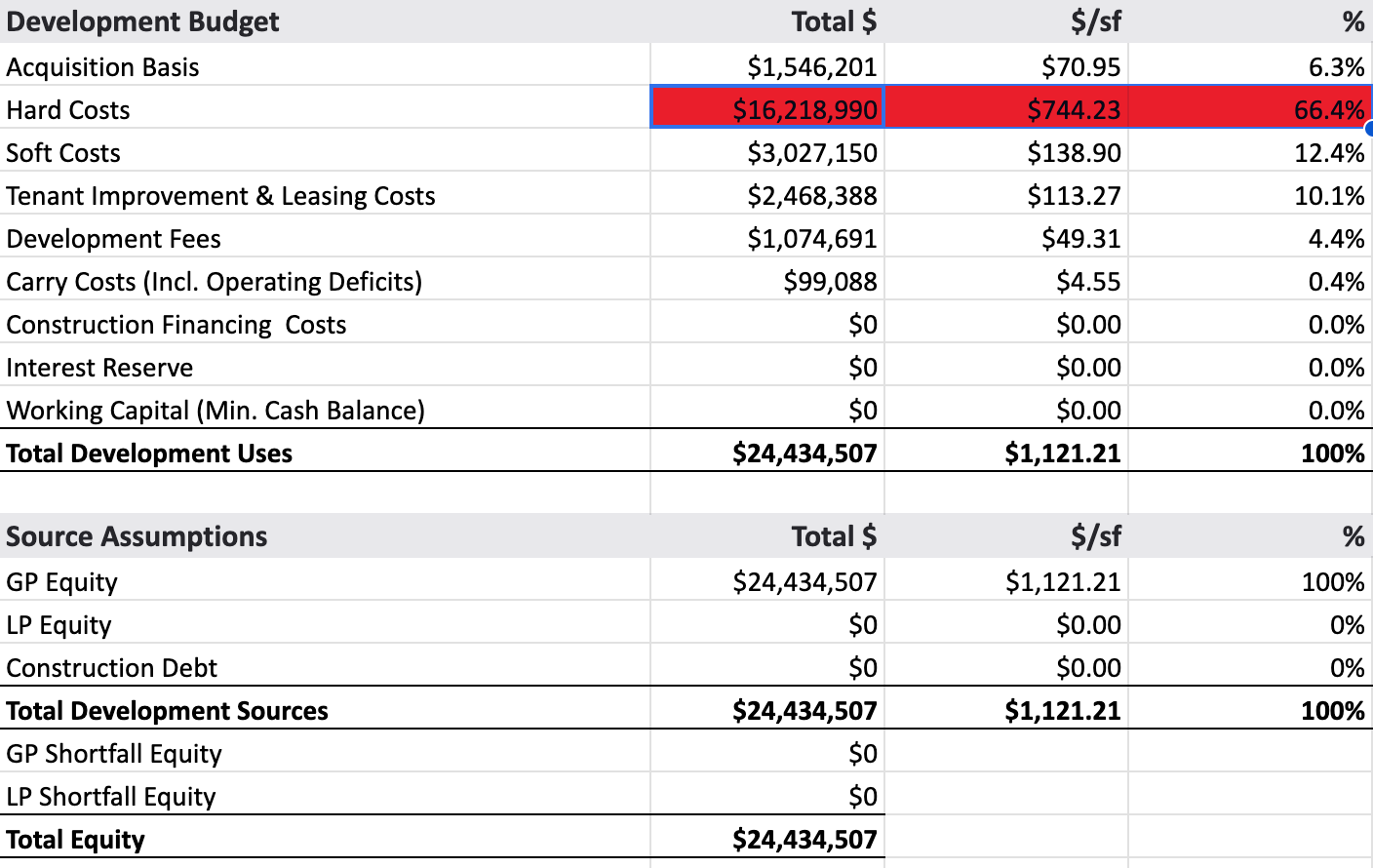

Here is the breakdown of the development budget.

Every time I pull up the deal sheets on Broad Street East and West, my stomach turns. The all in price per square foot, including acquisition basis, is $1,866 / psf. This is making the high-end, new build at $1000 / psf option a discount.

How can the hard costs be so much? We’ve already reviewed the major ones but lets enumerate the full list below.

- Structural repairs and reinforcements. This is at least 55% of the $16.5M.

- Mechanical system updates.

- Code compliance and safety upgrades.

- Facade and historic preservation.

- New roofs, not just membranes, but all new structures and parapets.

- All masonry work from the basements, to the roof. Tuck-pointing all the bricks. North of 90% of the bricks in these buildings have been touched by a mason.

- New utility tie-ins: water, gas, electrical ties.

- All new windows.

- A significant bill to Georgia Power to turn on electricity.

- Full walls needed to be emergency branched to stave off collapse.

There are two other significant factors that lead to the high dollars per square foot. Number one is speed. We have 116 days until the World Cup as of this writing. Contracts for Broad Street were signed 16 months ago. As the saying goes: you can have it good, cheap, or fast, but pick two. Well, on Broad Street we are paying for all three.

Secondly, another reason for the higher per square footage number, particularly on Broad Street East (the Broad Street West is a touch less stomach turning) is we hollowed out one of the buildings and made it a courtyard. That courtyard is now not leasable and alters the numbers.

More photos of the buildings before construction:

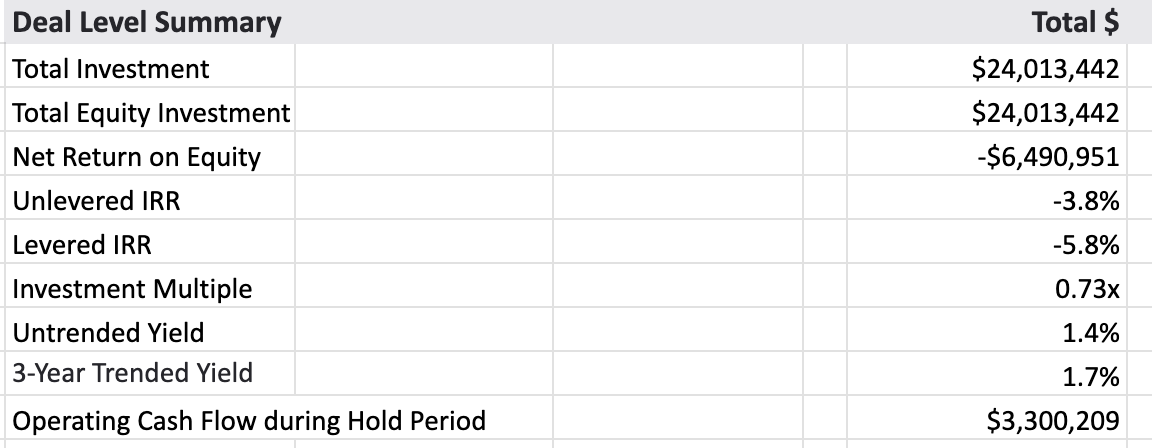

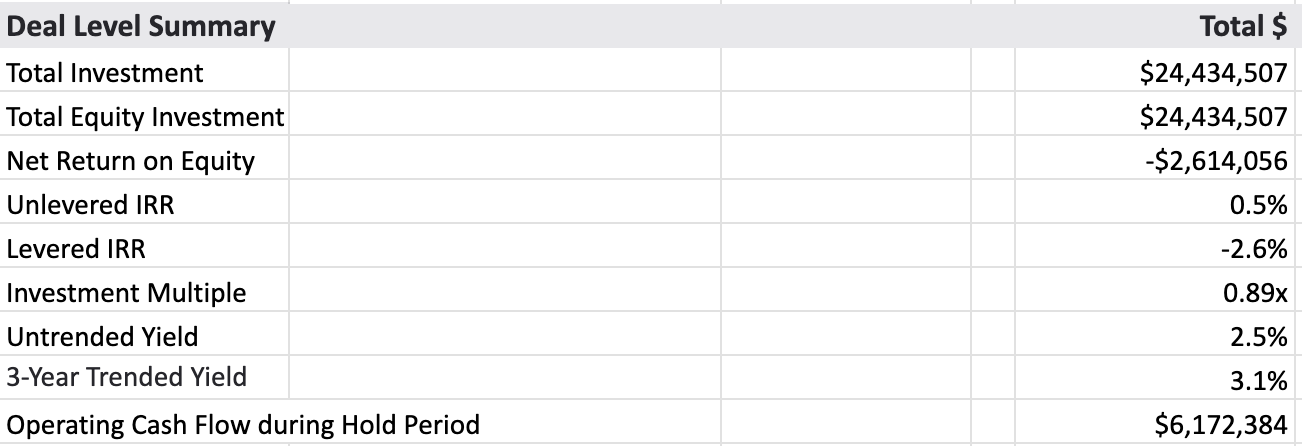

Assuming we can get market rate rents in South Downtown, the deal level summary is below:

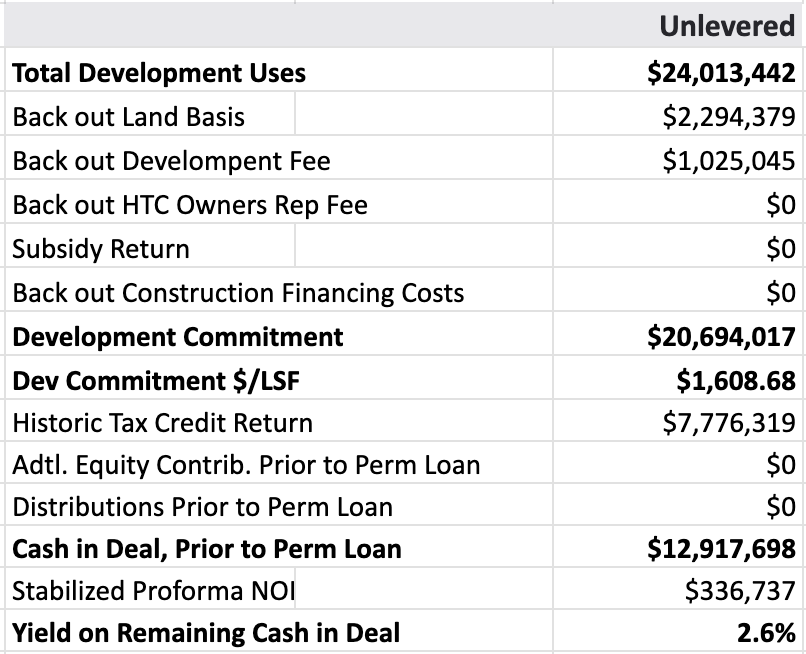

There is one silver lining to the rebuild on Broad Street: historic tax credits. The historic tax credits limit the damage but also require restoration and rebuild to a standard almost never seen in new construction. Here are the numbers after the historic tax credits get allocated. Assuming we can lease out everything, we squeak out a return of capital of 2.6% a year when it is fully leased at market rates.

Here is a design of Broad Street East’s future state.

Now, let’s walk across the street to Broad Street West.

Broad Street West has a celebrated history similar to its relatives across the street. The infamous Paul McCartney story and his Run Devil Run album took place on Broad Street West. If you don’t get anything out of this article, at least read this fun story about Paul McCartney naming his album after Broad Street. There’s so much more history, but I promised myself earlier to not delve into on this post.

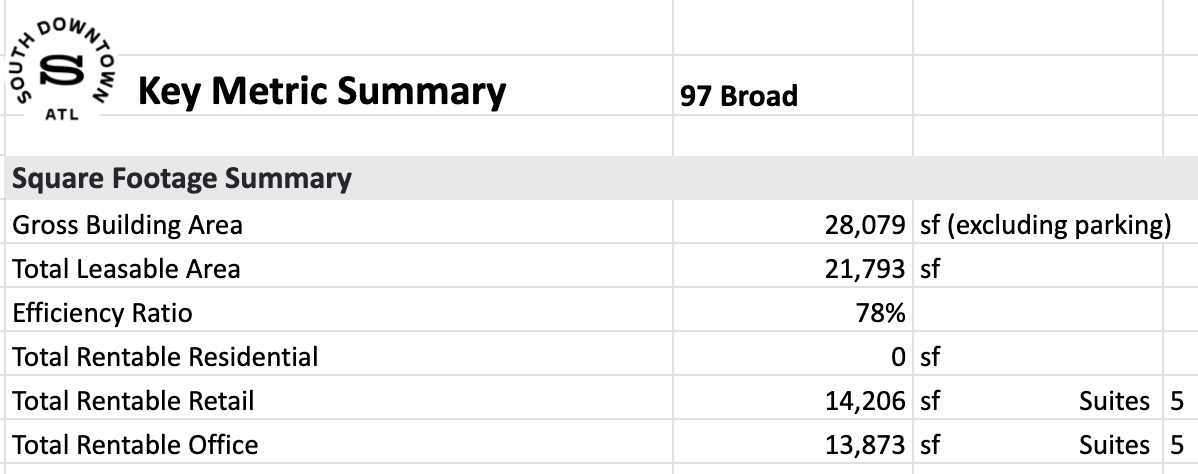

Let’s start with the high level key metrics:

Broad Street West has two more rentable office suites than Broad Street East. There is a three story building on the West side and we didn’t hollow out a building with a collapsed roof. These factors increase the efficiency ratio and total rentable space.

Alright, hold your breath…here comes the development budget.

The hard costs are pretty similar to Broad Street East but because there is more square footage the costs psf comes down. This is a good point to reiterate: this investment is only going into a much smaller, finite space. We do not get scale with these numbers making the investment harder to pencil yet producing a built environment one would be hard pressed to find in Atlanta.

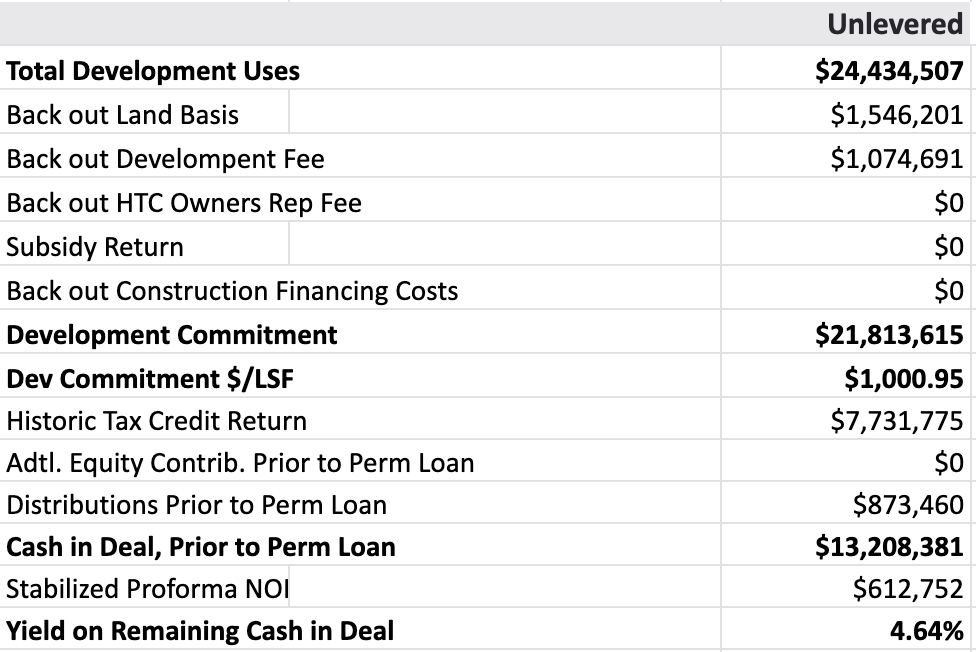

Here is the deal level summary.

But don’t forget, historic tax credits relieve a portion of the heart burn.

Here is the arithmetic with the historic tax credits.

So far we have two restaurants leased on Broad Street West. That includes Brew House Cafe, here’s the announcement, and Mule Train, here is their announcement.

Now that we’ve gotten through the dollars and sense (kind of) let’s go back to see what the value of the buildings would be assuming the same cap rate from the example above. The cap rate from the prior example above was 5%. This occurs in a proven, validated, and stable environment. At this point in time, South Downtown is not described in that manner. But for the sake of the example, let’s keep it at 5%.

Assuming we leased everything out at downtown Atlanta market rates, got the building "stabilized" and achieved the projected NOI number for Broad Street East of 336,737 / .05 = $6.7M and for Broad Street West 612,752 / .05 = $12.2M.

So why are we doing this? Why put money into downtown that has so much risk with so little upside? Why am I spending prime career years hawking downtown real estate in Atlanta?

The German development gave our city a massive gift in that they produced a once-in-a-city’s-lifetime-opportunity to transform our dilapidated downtown not through a generation or two, but in a half decade or so. This is like playing Mario Kart and always having the mushroom power surge on the entire time. We know this can’t be done alone. The true heroes of this unproven and wildly risky endeavor are the courageous restaurant and retail shop owners putting their small business enterprises on the line to bet on Atlanta and our downtown. The true heroes are the entrepreneurs who have decided to move their headquarters to South Downtown where just about anywhere else in the city would be 10x easier to build right now. Atlanta is refueling our enterprising tank with a refreshed historic downtown engine focused on locals. This endeavor is bigger than one person, one decision, or one business. It is a collection of every entrepreneur, every restaurateur, every visitor, every resident, and every South Downtown employee who believes these 16 acres, 10 city blocks, and 50+ historic buildings will create a change in our city not since the Beltline started or the Olympics arrived. I believe the impact will be greater than both combined.

Only time, heart, energy, urgency, and patience will tell.

South Downtown is your downtown!